As The Book Review went into press for its children’s issue in November last year, Nabaneeta Dev Sen lay dying, and breathed her last on November 7, 2019 after a prolonged battle with cancer. It was too late to include an obituary, but a children’s writer as prolific as her surely deserved one. It is not too late, however, to recall or commemorate her as an academic and writer who remains a household word in most Bengali homes in which people read Bangla for pleasure or in pursuit of scholarship. Those who knew her personally, however, reminisce mostly about her larger-than-life personality. Like most reputed writers in Bengal, she wrote both for adults and children, and her oeuvre comprised novels, short stories, poetry, drama, humour writing, travelogues and children’s fiction. She was the recipient of the Rabindra Puraskar, the Sahitya Akademi award and the Padma Shri among many others, but what is relevant in this context is the Big Little Book Award she won in 2017 for her children’s writing.

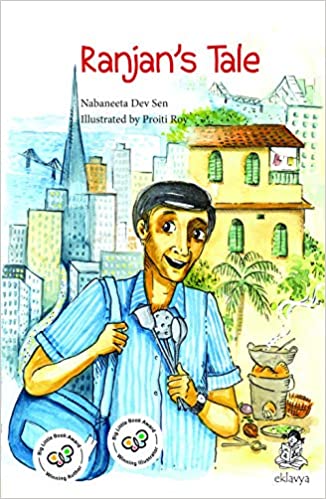

Ranjan’s Tale (a short story that has been published by Eklavya as a book for children, therefore the italics) is not among the best of her stories for children. But it warrants comparison with innumerable stories in Bangla with the same subject—the child protagonist’s resistance to school and studies. This has been a favourite theme with children’s writers since the beginning of the twentieth century, violating Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar’s compartmentalization of the good boy–bad boy prototypes among his first lessons in the children’s primer Barna Parichay (1855). And it has been reinforced by the real life experience of no less than Rabindranath Tagore among numerous others, who confessed in Chhelebela (My Boyhood Days) about his reluctance to study: ‘Even the awful thought that I should probably remain the only dunce in the family could not keep me awake.’ Many child protagonists in Bangla rebel against family and school pressures about doing well in studies which will supposedly open out the road to worldly success in the distant future, placing before them role models who are the epitome of good breeding and diligent studiousness. But despite showing irreverence for school and the education system per se, for most of the child protagonists, trying to escape from it remains a fantasy, and playing truant from school (and therefore home) amounts at best to an adventure in the outside world. These are often enabled by domestic servants, streetside acquaintances like magicians and jugglers or dropout uncles and cousins, but they also ensure their return to the safety and protection of their homes and schools, and such trysts remain brief interludes in the drudgery of their regimented lives.