In the making of Rabindranath Tagore’s public image, apart from the voices of the critical establishment and the poet’s own forms of self-projection, the reminiscences of those around him also played a part. A compulsive globe-trotter, Tagore often travelled with companions who knew him closely, and were privy to intimate glimpses of the man behind the mask. One such co-traveller was Nirmalkumari Mahalanobis, wife of eminent statistician Prasantachandra Mahalanobis.

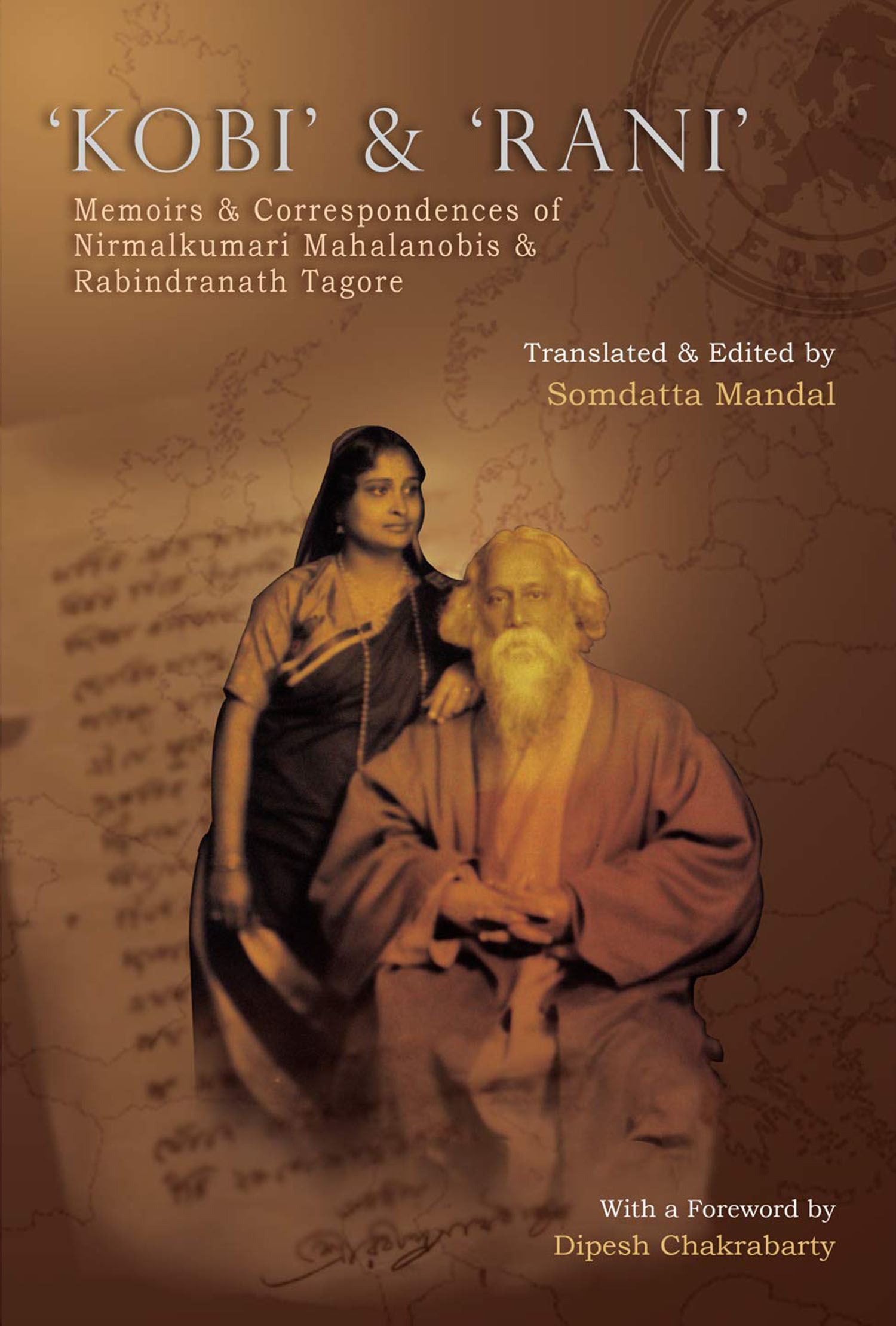

Part of the inner circle that surrounded the poet, she enjoyed a special, affectionate relationship with him during the last 15 years of his life. For those keen to know more about the human being behind the public stereotype of the revered ‘Gurudev’, the present volume offers rich fare. Compiled here, in Somdatta Mandal’s lively English translation, are Nirmalkumari’s memories of her experiences as part of Tagore’s entourage during his travels to Europe and Southern India. Alongside, the book also includes a selection of letters from ‘Kobi’ (Nirmalkumari’s term of address for Tagore) to ‘Rani’, the name by which he affectionately called her; and three other essays on Tagore, written by Nirmalkumari.

Published in 1969, the first memoir in this collection, Kobir Shonge Europey (With the Poet in Europe) refers to Tagore’s sojourn in different parts of Europe, between May and December 1926. The second, Kobir Shongey Dakshinatye (With the Poet in the South), appeared in 1956, and recounts Tagore’s visits to Ceylon and the southern parts of India in 1928. The third section, Pathe O Pather Prante (On the Road and Beyond It), contains 60 of the almost 500 letters to ‘Rani’ that Tagore published in 1928.

Nirmalkumari’s memoirs of the ageing icon, culled from her extensive travels with him, are embellished with extracts from correspondence, anecdotes and lively commentary. They evoke entire social, personal and political worlds, through vivid episodic glimpses. The narration is racy and engaging, laced with a distinctly feminine wit. In one episode, Rani bursts out laughing when Tagore vomits on board ship after pretending not to be seasick. In another, he protests when she finds it funny to see him wearing a wristwatch purchased by Rathindranath in Switzerland. ‘“A wristwatch on your hand looks quite unnatural.” “Why? All of you wear wristwatches, so what is my fault? Once, in Santiniketan, I had wanted to learn how to ride a bicycle; and Bouma [Pratima Devi] had also laughed at that.” I replied, “It really is something to laugh at. I cannot even imagine you wearing a wristwatch and riding a bicycle.” “Come on. You really have a very conservative mind. Now you see me like this, but once upon a time, did I have less physical strength than others? Did you know that back then, I could swim across the Padma?”’ (pp. 87-8).

Such episodes humanize the poet, presenting ‘the lighter and more domesticated side of Tagore’, as Mandal says in her Introduction.

Kobir Shonge Europey recounts the journey to Europe by ship, Tagore’s meetings with iconic figures such as Romain Rolland, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein and Moris Winternitz, and his exposure to aspects of European art, culture and education. In Austria, he is struck by the grandeur of western classical music, and in Germany, by the inclusiveness of the educational system, where the needs of children from underprivileged backgrounds are recognized. Most controversial is the visit to Italy under the watchful eye of his host Carlo Formici, one of the two Italian scholars who had visited Santiniketan with books from Mussolini. Formici’s ploys, including attempts to shield Tagore from anti-Mussolini groups in Italy, to get him to say favourable things about Mussolini, and to tamper with his press statements, place the unsuspecting poet in an awkward position with his followers. It is through the active manoeuvres of his travel companions that Formici’s designs are ultimately thwarted.

Kobir Shongey Dakshinatye includes an account of Tagore’s meeting with Aurobindo, and his visit to the luxurious palace of the king of Conoor. At the time, he was composing some of his major works, including Yogayog and Shesher Kabita. In the letters, Tagore’s felicity with language brings to life not only the human world, but also the vital presence of nature in his mindscape. The epistolary form enables a wide range of possibilities, but also creates a certain vulnerability for the writer, because it opens a door between public and private worlds. Dipesh Chakrabarty, in his Foreword to the collection, reminds us of Nirmalkumari’s complaint that prior to publication, Tagore had deleted the more personal parts of these letters, which in their original form had revealed his private self and deepest emotions.

Forms such as memoirs and letters have the potential to combine fact with memory, imagination, fantasy and desire, in ways that unsettle the conventional ‘truth claims’ of more formal genres such as autobiography. Memory becomes a site where, in place of reliable certitudes, we encounter uncertainties and a blurring of lines between fact and imagination. Coloured with emotion and desire, memoirs and letters can disrupt the claims of intellection and objectivity. That accounts for the special appeal of this collection, because it defies straightforward academic readings.

Somdatta Mandal’s translation keeps the informal, conversational tone of the Bengali original, making this volume an enjoyable read for the general reader, as well as a valuable resource for Tagore scholars. Some unfortunate editorial lapses apart, ‘Kobi’ & ‘Rani’ offers a commendable addition to the archive of Tagoreana.

Radha Chakravarty, writer, critic and translator, is Professor of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies at Dr BR Ambedkar University, Delhi.