Balbir Madhopuri lives in New Delhi. He grew up in Doaba, a region of Punjab known for its high population of Dalits. He has not forgotten his years of struggle against economic hardship and caste discrimination, but he does not advertise his pain and uses it instead to generate light and hope. In fact, he recalls with warmth the occasions when support came over the high barriers of caste, as when a Brahmin teacher reached out to him with affection and encouragement. It is a measure of Madhopuri’s integrity that he has chosen to live without bitterness, facing up to the demons yet not letting them eat him out.

Raj Kumar Hans in his introduction to the book correctly notes that Madhopuri staves off cynicism and so his poetry, despite the pain and anger, is ‘a calm expression of his understanding’ (pp. 10-11). Many victims of oppression become double victims, first the oppressor’s and then of themselves when they internalize oppression and allow ressentiment—as Nietzsche describes it—to possess them.

Relocating to Delhi probably helped Madhopuri. He entered a more accepting, cosmopolitan community. A vaster, more complex reality was revealed to him as he read across a variety of literature, particularly Hindi, Marathi and Soviet. His youthful Leftward leanings–he became a member of the CPI student wing in 1974—now flowered and he became a thorough humanist and a believer in rational progress. Those leanings had deeper emotional roots in his childhood. Especially formative was the influence of his grandmother whose instinctive atheism was infectious. Madhopuri’s poetry testifies to the skills, gained over a long time, of balancing emotion and reason: there is conviction without dogma, empathy without mawkishness.

The most plausible explanation of his freedom from bitterness would be that he took to writing Dalit poetry self-consciously quite late as a poet. Dalit consciousness in his case is not raw and reactive but mature and mellow, the experiences having been intellectually and emotionally processed. Of the three phases of his poetic journey, the Dalit phase is the last and the ripest. The first was the phase of romance, the second of grappling with the turmoil and terror that reigned in Punjab in the 80s. He has practically disowned the poetry of the first phase as immature; My Caste–My Shadow does not include anything from this phase.

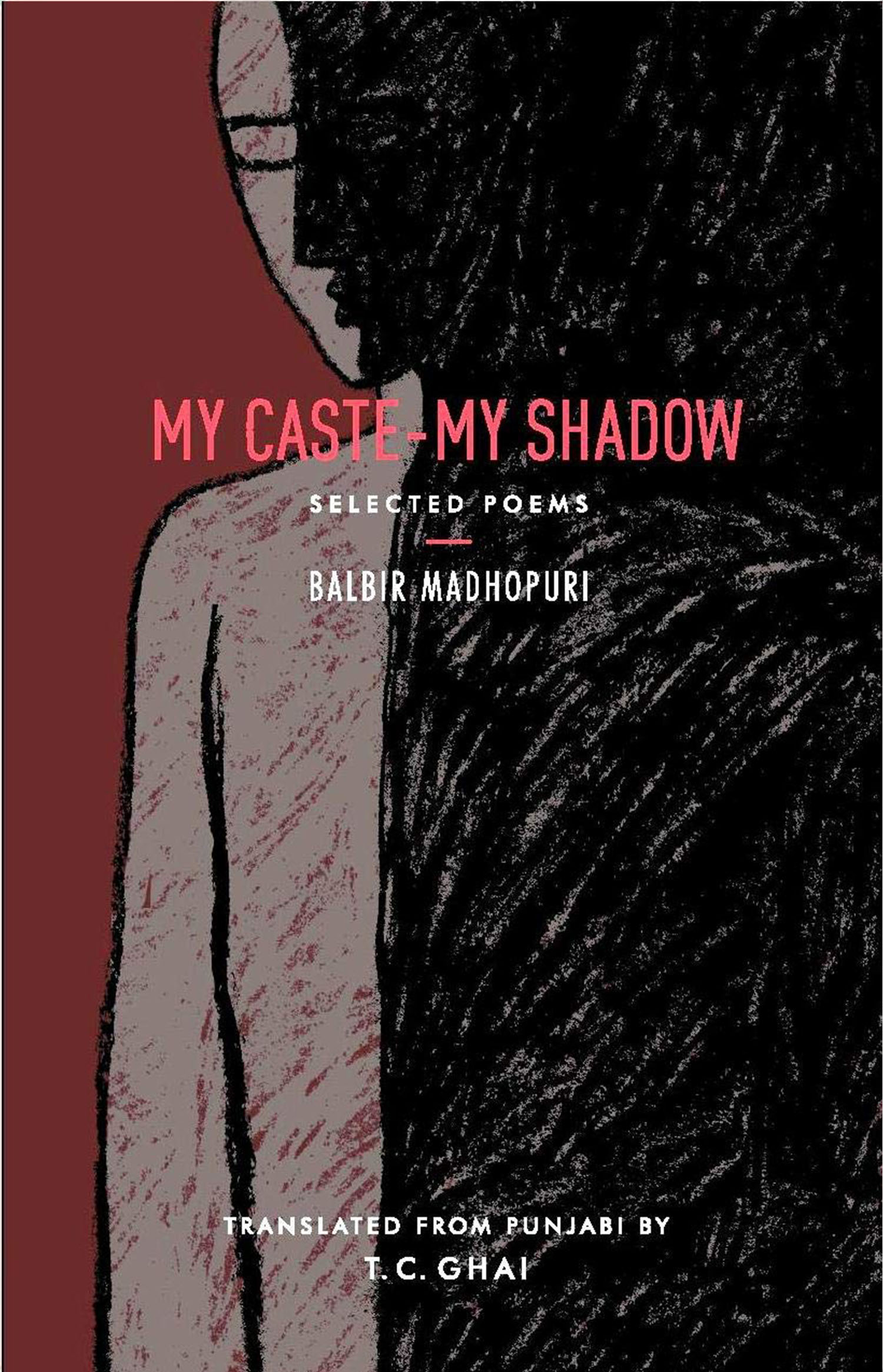

The book, which carries TC Ghai’s translations of Madhopuri’s selected poems, is largely based on selections personally made by the poet and published as My Selected Poetry (Meri Chonvi Kavita, the title in Punjabi) in 2011 and again in 2019. Madhopuri picked up 41 poems, mainly from the two books of poetry, Tree of the Desert (Maruthal da Birkh, 1992) and The Smouldering Abyss (Bhakhda Patal, 1998). To these he added a few unpublished poems to produce a representative map of his journey as a poet. Ghai has chosen 34 out of the selection. He has also rearranged the order of the poems.

Madhopuri’s work was noticed outside Punjab when an English translation of his autobiography Chhangya Rukh (2002) was published by Oxford University Press in 2010 titled Against the Night. The autobiography cast a shadow on his poetry, so much so that he is still better known for it than for his poetry with which he had started publishing. Ghai’s translation may help the poetry reclaim its fair share of recognition vis-à-vis the autobiography.

But will it? The question cannot be answered easily. One has to reckon with the state of literary translation in India and the situation of a particular translator and of a translation with reference to it. By no means is it a happy state. Translators work in relative isolation, motivated by little more than personal fondness for their work (some of course have career designs and a few are dogged by need). An indigenous discourse on translation remains, in terms of extent and continuity, meagre and patchy. Add to it the near absence of translation criticism, which means there is little nurturing and no nourishment. The usual result is that while some translators are scared of even decently exercising the translator’s licence (which any outstanding literary work demands), there are those who would pervert the licence into licentiousness. With the field of translation not ripe, the harvest is either stunted or etiolated.

The absence of a community of translators shows also in the practice of insufficient reading of a given text so that the translator’s—to some extent ineluctable—interpretation risks becoming a distortion. This is promptly noticed by an attentive reader if he happens to place the translation beside the (so-called) original. For some reason that I have not been able to unearth, some translators like to believe that the reader of the translation will never reach for the original or check out another translation. Were they not to believe this, they would be free from the vice of casual substitution to which they succumb when they are disinclined to dig their heels in a text and wait for sense to dawn.

By and large Ghai’s translations of Madhopuri’s poems are not just fairly good but are quite truthful—whatever that means in the arts—and nuanced. But here and there he yields to the seduction to quickly get over with the work that needs patience more than anything. Perhaps he is too enamoured of a fancied pair of foreign eyes looking over his shoulder at the translation and uninterested in the specific character of the native text with its peculiar semantic and sonic evocations. So he renders ‘mera buzurg’ as ‘my old man’ (p. 55), which might allude to a partner but surely does not to a parent. The image of an electricity cable passing over a tree which has been pruned so as not to touch the cable is recast to make the tree ‘support’ the cable (p. 37), the ‘translation’ subverting the very intention of an image suggesting undeserved violence by replacing it with another that makes the victim into a collaborator. Elsewhere the punctuation instead of charting the way seems intended to bewilder the reader—and for no purpose (p. 44). The most painful is a substitution that replaces something sublime with a lowly absurdity: the grand adventure of the colourful fish from beyond the seven seas which have returned having ‘tongued the rocks of infinity’ is reduced and perverted to something intriguingly (at least for this reader) as vacuous as the experience of ‘having licked the stones of self-indulgence’ (p. 34). By no stretch of imagination can I see any equivalence between ‘aseemata’ (infinity, boundlessness) and ‘self-indulgence’.

Not that Madhopuri’s poetry does not have its shortcomings. Its quality is uneven even as its range is impressive: home, family, trees and winds, friendship, terror, rage, despair and hope, myth and legend, the village and the cosmos—it moves effortlessly in all those places, outer and inner. There are moments of stunning charm: colours steal upon flowers out of the silent void, the stars of thought ascend the mind’s firmament, pathways swallow the footprints, a friend is distant like the sun and near as the sunshine. But then the poet goes after something he has not intellectually worked out, such as globalization, and the poem doesn’t know where to go. The images get entangled, contradicting each other for want of clarity (‘Sanskriti’, pp. 41-42).

Ghai has been working tirelessly to place modern Punjabi poetry on the world’s poetry map. He has produced translations of Pash and Lal Singh Dil. It is time to engage with his work critically and competitively.

Rajesh Sharma is an essayist, critic and translator. He is currently Professor and Head, Department of English, Punjabi University, Patiala. He writes in English and Punjabi, and translates between Punjabi and English and from Hindi to English. He teaches literary theory, modern European fiction, modern world poetry, and film studies. His forthcoming book is On Aristotle’s Poetics (Copper Coin, 2021).