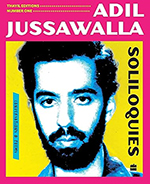

With Adil Jussawalla’s Soliloquies, Thayil Editions has delivered its first number. It is an aesthetically designed book with a frail binding. The first part is a long conversation, illuminating and heart warming, between Jeet Thayil and Jussawalla. The second is a precocious work of free verse the poet produced in his late teens. Together the two will enrich the archives of modern Indian English literary history. Jussawalla is a gifted photographer as well: the keen, astonished eye probably comes from his mother who was a student of Nandalal Bose at Santiniketan.

Jussawalla recalls the recognition his talent and efforts received from his teachers. The guidance came in gestures and appreciative hints, and encouraged him to not only endure but make his way. So there is a gnomic irony in his self-perception as a laureate of failures. The truth is he was always correcting his course, which means he had a feeling that his destiny lay elsewhere. He would drop out of architecture, leave and then return to Oxford, start a novel only to abandon it—as if he had to arrive somewhere altogether else. Today he is more than the sum total of those successful failures. He arrived long ago and abides in his singular place with a quiet, observant style and a sensibility that is radiantly humane.

‘I’m the original hippie,’ Jussawala tells Thayil. His questing restlessness is a sign of freedom from complacency and inspires the intellectual integrity that distinguishes his nuanced view of Marxism. He sees what he sees because he wears no blinkers and can live with ambiguities. He coolly affirms, even after seven decades, the power of the ‘primal mystical experience’ of his teenage years and contemplates the mystery of the Word. It is not by chance that he speaks of renouncing smoking and drinking as a ‘conversion’.

The conversation places a life’s work in context through anecdotes fished out of a sea of memories. Nissim Ezekiel, Mulk Raj Anand, Dom Moraes, Gieve Patel, Saleem Peeradina, Arun Kolatkar, Manohar Shetty, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Eunice de Souza, the Beat poets and others walk in, lending the warmth of their breath to the tales. An age of literary history comes to life in narratives almost oral in their pulsing charm. The intensity of the 1970s and the uncertainties of the 1990s return to register themselves with greater force of clarity in the country’s remembered past.

Yet Jussawalla does not romanticize the past. Like Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen in their ‘Calcutta’ (as Kunal Sen tells us in his book Bondhu), he has felt acutely the absence of an intellectual community in his ‘Bombay’. You sense a seething bitterness when he speaks of buyers of poetry books: ‘We are not as generous with one another as we are led to believe. It’s okay to believe in the community of poets but that little bit of effort to buy one another’s books doesn’t seem to happen.’

And he raises an important question that is yet to be adequately answered. How does a writer’s experience of departure from his country shape his writing? How would Nissim Ezekiel, Dom Moraes and Jussawalla himself have written had they never left India? One thing is clear: Soliloquies would never have been written. It needed the raw taste of distance, an experience of the void and a craving for plenitude that the consolations of home might have blocked.

and short pieces of the order of middles. The mixture of elegant expression and hard fact is a reminder of the happy union of journalism and literature that the new barbarism of instant updates has long since swallowed. At its finest, Jussawalla’s prose reminds you of the inimitable Ved Mehta and Khushwant Singh, even of Joseph Mitchell and EB White. It has the light, grace, candour, considerateness and empathy of a cultivated conversation. But unlike theirs, it bubbles with numerous literary references spontaneously conjured by a sensibility that a lifetime given to the delights of reading has formed. The best of Jussawalla is to be savoured at leisure. A sense of the time passing hangs like mist over several pieces and the odour of obsolescence is uncannily fascinating.

and short pieces of the order of middles. The mixture of elegant expression and hard fact is a reminder of the happy union of journalism and literature that the new barbarism of instant updates has long since swallowed. At its finest, Jussawalla’s prose reminds you of the inimitable Ved Mehta and Khushwant Singh, even of Joseph Mitchell and EB White. It has the light, grace, candour, considerateness and empathy of a cultivated conversation. But unlike theirs, it bubbles with numerous literary references spontaneously conjured by a sensibility that a lifetime given to the delights of reading has formed. The best of Jussawalla is to be savoured at leisure. A sense of the time passing hangs like mist over several pieces and the odour of obsolescence is uncannily fascinating.

A prose writer is boring when he is not penetrating. The demands of a regular column don’t always inspire insight. Neither does insight easily adjust to the size of a column. Reading these pieces makes you see how the pressures of journalism can eat into literary talent. But the world is hard and unforgiving; it doesn’t happily accommodate unworldly gifts.

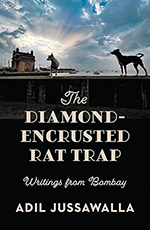

Those gifts exalt several pieces collected here. ‘The Diamond-Encrusted Rat Trap’ discloses an amazing story-teller lurking in the essayist’s art. ‘Heeling Process’ is a model for anyone learning to know with feeling and care. ‘Cringing in the Rain’ dexterously places humour, erotica, the mildly grotesque and poetry on one platter. A stereotype is overthrown with a gentle flick in ‘Voices from the Homeless Areas’. ‘The Bombay Within’ exemplifies the review that really does justice to a book because it is written with love and labour. But ‘O City, City…’ reflects a helpless writer’s boredom; by a preternatural chance, Donald Trump makes a guest appearance in this piece from 1993. ‘Mulk Raj Anand: Agile Neighbour’ sings with a fraternal intimacy.

In comparison, the writings assembled in Body of Evidence: In Sickness and Health do not represent Jussawalla’s range, distinction, and limitations fairly. The title with its oppressive grey neither pleases nor soothes. The see-through paper and the shoddy cutting deepen the gloom. The pieces, most of them very short, have been put together with exceptional indifference: most do not rise above the level of middle-brow middles. You wonder how many particles will settle in some recess of your sensibility if not in your deep passive memory. Rarely do you witness something lasting being abstracted out of evanescence, the kind of thing Jussawalla nimbly accomplishes in so many pieces elsewhere. The book is somewhat saved by ‘Granta’s Body’, an erudite and curiosity-laden review, and by the surrealistically titled ‘From the Cupboard of the Flesh’, which combines a fine moral stance with an unadorned idiom.

The pieces in these three books mostly follow the principle of associative wandering. The wandering consciousness, however, does not always remember where it had started and for what it is wandering, something that Montaigne and Emerson rarely forgot. In their case, every circling was meant to scoop deeper and see farther. But then they were not chasing deadlines. Neither did they have to write a word less or more, free as they were from the tyranny of demands extraneous to the writer’s art but innate to the journalist’s profession.

Rajesh Sharma is a literary critic, essayist and translator. He usually writes in English and Punjabi. His latest book, Dekhna Hoga, is a collection of poems written in Hindi.