1857 is etched in the historical memory of India, particularly of Indian Muslims, as a singular event that ushered in a tectonic shift in Indian history and transformed their fate forever. Their claim to equal citizenship, let alone supremacy, was permanently eroded and the process of their minoritization was slowly set in motion. Nineteenth-century Muslim intellectuals like Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Mirza Ghalib had a vague sense of it. But others, especially those writing in the wake of the 1947 Partition, could trace the genealogy of this erosion more clearly. Intizar Hussain, in fact, traces the 1971 Partition of Pakistan as well as 1947 to the events of 1857 in his novel Basti and the short novella Dastan. Zakir, the protagonist of the novel Basti recurrently ruminates over the events of 1857 in the backdrop of 1971 reversals faced by the Pakistani army in Bangladesh.

It is not surprising, therefore, that translator Ali Khan Mahmudabad reverts to a work of historical fiction about 1857 to reaffirm the nationalist credentials of his forefathers, the Rajas of Mahmudabad. The Estate (taluqdari) of Mahmudabad was founded in 1677 by Raja Mahmud Khan, a descendant of the first Caliph of Islam. Muqeem-ud-Daula Raja Nawab Ali Khan was the Raja of Mahmudabad during the 1857 uprising. The Rajas of Mahmudabad are known to be great connoisseurs of art and poetry, the translator, Ali Khan Mahmudabad, being one of them. A poet and scholar, Ali Khan’s first book Poetry of Belonging: Muslim Imaginings of India, 1850-1950 (2020) is a testament to his erudite and insightful understanding of Muslim articulations of identity and belonging through Urdu poetry.

What is indeed surprising, however, is the fact that the writer he chooses to translate should be so obscure in the present day consciousness of the Urdu literary world. Khan Mahboob Tarzi (1910-1960), we are told in an insightful introduction by Mahmudabad, was a prolific writer, who wrote Urdu fiction and produced more than a hundred novels that include political, historical, detective, suspense, sci-fi, romance, and erotica.

Tarzi had his initial schooling at the Wesley Mission School and the Ameeruddaula Islamia College and received his higher education in Science from the Aligarh Muslim University where he began publishing his stories in journals like Nairang-i-Khayal, Mahnama-i-Saqi, and Alamgir. From working as a supervisor in a lock factory in Aligarh, attempting film-making and direction in Calcutta, serving in the army, working at the Radio Station in Lucknow and Delhi, to even trying his hand at journalism, Tarzi donned many hats in his versatile career. He wrote regularly for Naseem Book Depot’s journal Sarpanch and made a name for himself, along with writers like Wahshi Mahmudabbadi, Nadim Sitapuri, and Ziya Azimabadi, for writing fiction on popular demand.

The ‘Author’s Preface’ is mostly a paean to the valour of Raja Nawab Ali Khan of Mahmudabad. Tarzi showers praise on the Raja in these words, ‘This martyr of the freedom movement took up arms against the British, tried to foil their devious plots and amassed a great army to defend Lucknow’ (p. xxxviii). Tarzi’s idioms here are clearly soaked in the post-Independence nationalist discourse espoused by the Congress Party and have the advantage of hindsight.

The Break of Dawn was originally published in Urdu as Aghaaz-e-Sahar in 1957, the centenary year of the event, now officially celebrated as the First War of Independence. If Intizar Husain’s novella Dastan captures the reversals suffered by Bakht Khan, the Rohilla chief from Delhi region and leader of rebellious soldiers, Tarzi, an icon of Lucknowi tehzeeb, decided to capture the events as they unfolded in the Awadh region. Like any other work of historical fiction, the novel has real historical figures like the Rajas of Mahmudabad and Ramnagar Dhameli, Begum Hazrat Mahal and her son Birjees Qadr as its protagonists. Drawing heavily from official histories and British gazetteers to develop the frame of his narrative, Tarzi imbues it with his rich imagination and weaves a story of suspense, action and romance around historical events.

The story of the novel centres around Riyaz Khan, a young soldier in the army of the Raja of Mahmudabad who had decided to side with Begum Hazrat Mahal in her revolt against the British in 1857. While the fire of rebellion was set ablaze by the soldiers from Meerut who had marched to Delhi to declare the Mughal King Bahadur Shah Zafar their leader, its heat reached far and wide and the entire region of Awadh went up in flames. Riyaz Khan is presented right from the beginning of the novel as a brave soldier, ready to die for the honour of his people. But more than this, Riyaz Khan and his fellow soldiers represent the moral vector of their Raja. When his contingent comes across a group of British men and women trying to escape the turmoil, Riyaz stops his fellow soldiers from killing them, and reminds his men, ‘We are soldiers and we can only engage with soldiers. Just yesterday we swore before the major that we would only fight those who attack us’ (p. 6). Later, when an officer of another contingent, Dulha Khan, commands Riyaz and his men to hand over the prisoners to them, they clearly refuse. Jawahar Singh bravely retorts, ‘…we have made Raja Nawab Ali Khan our leader. He has ordered that English children, women and non-combatant men not be killed. They should be safely escorted outside district lines’ (p. 15). In the process of saving British civilians from fellow ‘mutineers’ and escorting them to the safety of Lucknow, Riyaz falls in love with Alice, a young girl in the group. Alice vows her loyalty to Riyaz, declaring him to be ‘a true patriot’ whose ‘actions will be remembered for generations to come’ (p. 83) The novel ends with Riyaz marrying Alice and the British granting amnesty to all those who had fought against them. The novel clearly bears a resemblance with Ruskin Bond’s A Flight of Pigeons (1978), which as the translator has rightly pointed out, is far superior in terms of craft.

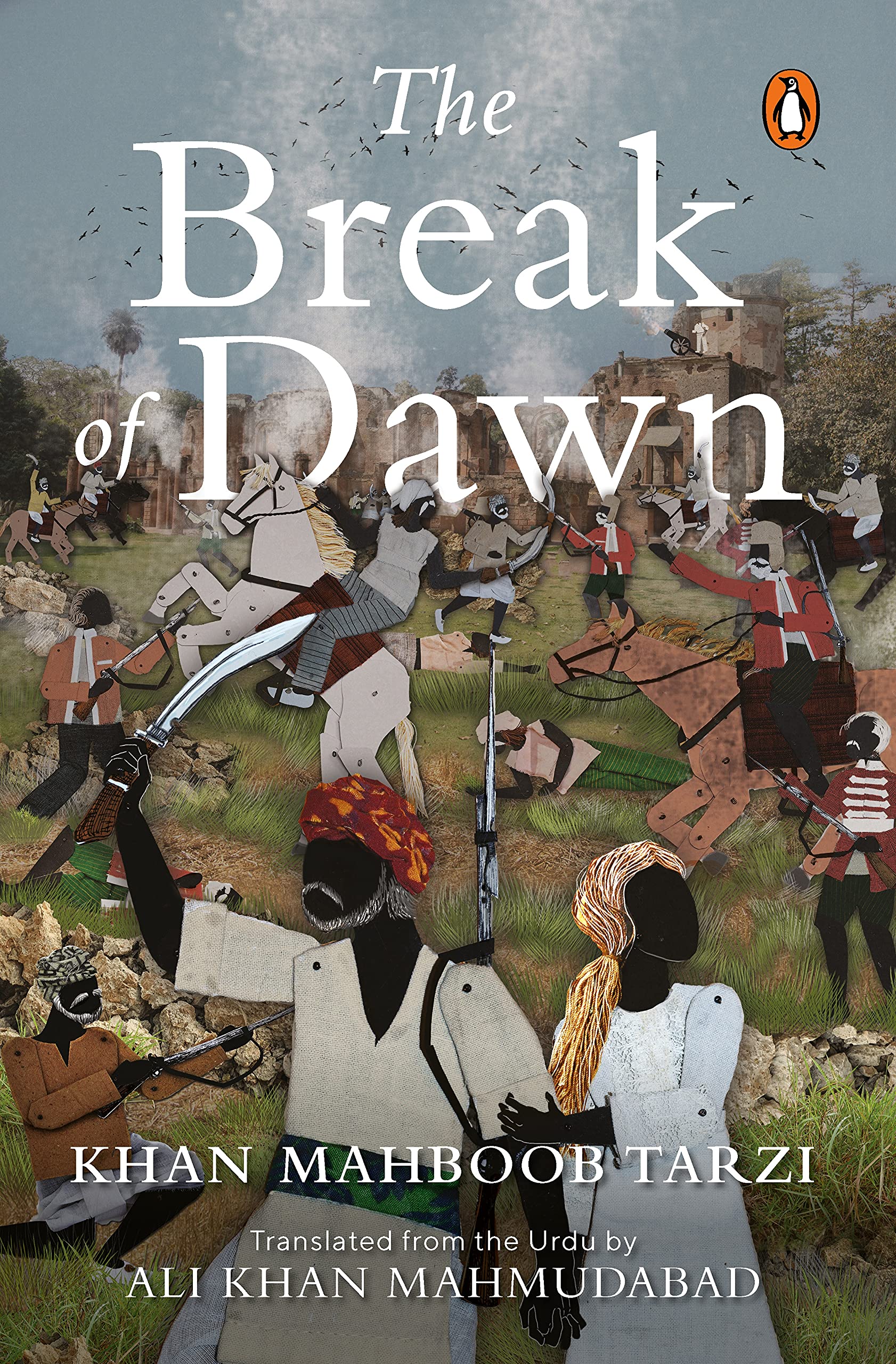

The choice of a text for translation is a vexed question in the discussion of the politics of translation. In this case, one may question the translator’s choice of text, which neither represents the best of historical fiction in Urdu, nor may necessarily be the best work by Tarzi and by the same token, may not be the best choice to introduce the author to a wider audience. The translator, Ali Khan Mahmudabad, makes no such claims either. The book is an act of love, of commitment and gratitude to the past and in this sense, as readers, we are enjoined to enjoy and appreciate the fine translation and the animating spirit behind it. The beautiful illustrations by Labonie Roy complement the narrative by adding an aura of suspense and charm to the actors, actants and actions of the novel.

Nishat Zaidi is Professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia. Her forthcoming work is Karbala: Historical Play, a translation of Premchand’s play.