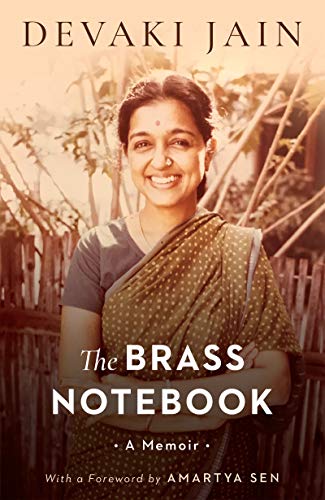

When a pioneer of the women’s movement in India opens up the window box of her memories, one can expect some startling revelations and some valuable historical perspectives. Devaki Jain delivers on both counts, making this candid and charming book an inspiration for its readers. Called The Brass Notebook, the immediate throwback is to Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook (1962), a mirror to the fragmented narratives that often comprise the inner life of women. Devaki brings her local version of pittalai or brass in Tamil, the language of her childhood. A vivacious eighty-seven years of age now, Devaki Jain has no hesitation in writing about her complex relations with her father, her abiding romance with her husband Lakshmi Jain, a ‘northerner’ she married against her father’s wishes, her occasional dalliance in youth, her early conviction that women ought to be ‘free’, and her accomplishments as a feminist economist in a male dominated sphere. The book is structured creatively, flowing through various experiences with ease, amply demonstrating that famous feminist slogan, ‘The personal is the political.’

It was my privilege to talk to Devaki Jain about her memoirs at a session of the Jaipur Literature Festival. I asked her about the term ‘before midnight’s children’ (p. 45) that she uses for people who carry remembrances of India’s swadeshi struggles, but who were too young to join the satyagraha. She offered a nostalgic account of two residents of the Sevagram Ashram who anchored her early political thinking. Devaki recalls, ‘They spoke about the simplicity and identification with the poor. They represented the spirit, the yearning and the effort to usher in Gandhi’s idea of a “second freedom”—freedom from deprivation through sharing with the poor’ (p. 51).

Self realization came rather rapidly because of a stint in England which included studying at Ruskin College, Oxford, largely a place for working class students managing the realities of economic hardship. Devaki’s eyes light up when she recalls the experience of learning from her new friends. Dressed in a saree, and from a traditional Indian home, Devaki was out of depth in such a community, yet fascinated by it. Concepts of race and colour, wealth and poverty, restraint and freedom came tumbling into the conversations and Devaki began to reflect seriously on the idea of a ‘free woman’, a persistent strain in her memoirs. Oxford was to be her academic ‘home’ many times, and over the years Devaki met the change agents of women’s empowerment in the western world—Gloria Steinem, Doris Lessing, Iris Murdoch, Alice Walker among others. In a poignant passage Devaki says, ‘Freedom and self reliance come with risk, and the life of a free woman cannot be insulated from hurt. Sometimes the most we can do is to learn not to be broken by our experiences, to rebuild our lives with what materials are at hand, bit by bit, slowly and patiently’ (p. 135).

I would have thought that Lakshmi Jain, Devaki’s life partner and a Gandhian economist, might have been an influence in bridging the gap between her orthodox upbringing and her desire to serve the underprivileged. In my conversation with Devaki on the JLF platform, there was a chance to go deeper into this pivotal relation in her life. She denies any ‘influence’, observing that their spheres of work were different; they respected each other’s choices and preferred to function independently. I ask if the economists of her time influenced her thinking. The chapters recalling friends and professional contacts bring up names such as BN Ganguli, Amartya Sen, Jagdish Bhagwati, Sukhamoy Chakraborty and KN Raj. Devaki says it was a fortunate coincidence that such brilliant economists were in Delhi at the time and discussing economic theory and policy. This probably sharpened Devaki’s conviction that women needed to be identified as a distinct category. Through the years of teaching at Miranda House and thinking anew about economics and the condition of women in India, a radical shift happened in Devaki’s formulations on gender based inequities. Her book Indian Women (1975) was to be a signpost for the journey henceforth.

Most people today would identify Devaki Jain with her path-breaking work on women’s labour. The term ‘feminization of poverty’ is attributed to Devaki Jain but she puts the record straight that she would rather emphasize the ‘pauperization of women’. According to Devaki, there are ‘three distinct elements: that women have a higher incidence of poverty than men, that women’s poverty is more severe than that of men, that a trend toward greater poverty among women is associated with rising rates of female-headed households’ (Women, Development, and the UN, 2005). Turning more personal, she recalls that the phrase she preferred to use was ‘poor women’ something that Marxist socialists thought was ‘demeaning’, others that it was an echo of ‘some dark Dickensian world of work houses and orphans’, yet others wondered if it was linked to Gandhi’s notion of Daridrnarayana (p. 160). Strong in her convictions Devaki Jain declares, ‘What we needed here was not new words but new nuances given to old words’ (p. 161).

Devaki Jain’s stellar track as a ‘feminist economist’ is presented with admirable restraint. Founder of the Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST) in New Delhi, and Chair of the Advisory Committee on Gender for the UN Centre in Asia-Pacific, she travelled widely. In 1997 Lakshmi Jain was invited to represent India in the newly liberated South Africa (p. 193), and Devaki speaks emotionally about meeting Nelson Mandela and participating in the reconstruction of the nation. Clearly, the experience left a deep impact. She seems driven by a passion for helping deprived women workers and guided international committees, Indian civil society organizations and research projects, making a mark at each point. In 2006 Devaki Jain was awarded the Padma Bhushan.

Despite such success, Devaki remains the sensitive woman with compassion for the poor. The memoir ends with two kinds of reflection. The first on the nature of her feminism, ‘We, Gloria (Steinem) and I, continue to swing together, even as we pass the ripe ages of eighty-five plus due to the grounding and belief in feminism and non-violence’ (p. 164). The second is about love and loss as she offers a requiem to those of her dear ones who have passed on, ‘Akka’ her mother, and Lakshmi, her soul-mate.

*Grateful acknowledgment to JLF for the conversation on The Brass Notebook, 18 December 2020. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ry9_1xvPnSY)

Malashri Lal, Professor in the English Department (Retd.), University of Delhi, has co-authored with Namita Gokhale, Betrayed by Hope: A Play on the Life of Michael Madhusudan Dutt (HarperCollins, 2020). She is currently Member, English Advisory Board of the Sahitya Akademi.