The ancient Sanskrit texts have many references to the practice of fine arts in India. But not many of the fine arts have survived through the ages. How¬ever, what was regarded as fine arts in ancient India cannot be included in the present day meaning of the term. There were sixty-four fine arts that in¬cluded physical culture, use of weapons, elephant riding, instrumental music, dancing, painting, body decoration, astronomy, magic, wood-craft etc.

Archives

Sept-Oct 1981 . VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2R. Parthasarathy, returning from ‘exile’, wrote ‘My tongue in English chains/I return, after a generation, to you.’ Taking this poem as a paradigm of Indo-English poetry, M. Sivaram¬krishna says in his introduction to this collection of critical essays on the work of eleven poets, ‘It is in terms of this triadic frame of reference…the transcen¬dence of Anglo-mania through an assertion of the Indian identity, the discovery of a ‘viable’ past and the residue of linguistic significance—that the following pages try to map out the features of the unchained tongue, that is Indo-English poetry today.’

This attempt to ascertain the worth of Saleem Peeradina’s poems must, neces¬sarily, be made in the context of recent Indian English poetry. Let me begin, therefore, by quoting from Chirantan Kulshrestha’s introductory essay to the critical anthology Contemporary Indian English Verse (New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann, 1980).

By training a political scientist, Dr Karkhanis has chosen a new field to work on. Here he explores the ‘significant relationship between the press and the Indian political institutions.’ His aim is to ‘analyse the role of the press in Indian politics’ and to assess its ‘impact on India’s governmental processes’, a chal¬lenging and a promising area of inquiry.

‘THE Forgotten Empire’ (Robert Sewell—London, 1900) is at present one of the most researched areas of South Indian history with Western and Indian scholars converging upon it. If at one end of the academic spectrum there is the grand

theoretician Burton Stein, one could locate M.H. Rama Sharma right at the other end of it.

THIS well researched book seeks to fill a gap in the historiography of religious movements and their leaders in modern India. Jordens uses all the known writ¬ings of Shraddhananda and a variety of other sources to paint a fresh and sym¬pathetic life of the Swami.

THIS book is a contribution to the grow¬ing literature of analyses of the Indian economic experience and attempts to explain the deceleration in growth since the mid-1960s. The author proceeds from a self-avowedly Marxist position, and is to be credited with offering theoretical explanations for different economic pro¬cesses, rather than mere descriptions.

The question why the rate of investment in the Indian economy has declined since the mid ’60s, and why it is not picking up are matters of considerable concern to policy makers. Successive Finance Ministers (including the one in the short-¬lived Janata Government) have been pro¬viding various incentives so as to encou¬rage investment in the private sector. But this appears to have had little impact.

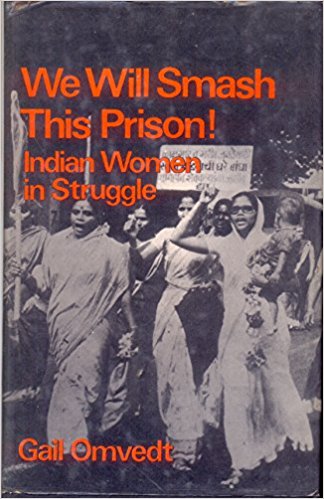

The book under review is an examina¬tion of the situation and struggles of women in Maharashtra, the most ‘Latin American’ of Indian states, in the mid-1970s. Although Maharashtra, the state surrounding Bombay, is the most indus¬trialized and capitalist in India, the position of women there reveals all the problems typical of the country: exploita¬tion and oppression based on caste, religion, feudal tradition and race (the adivasis are India’s Indians) add to the universal problem of women under peripheral capitalist development.