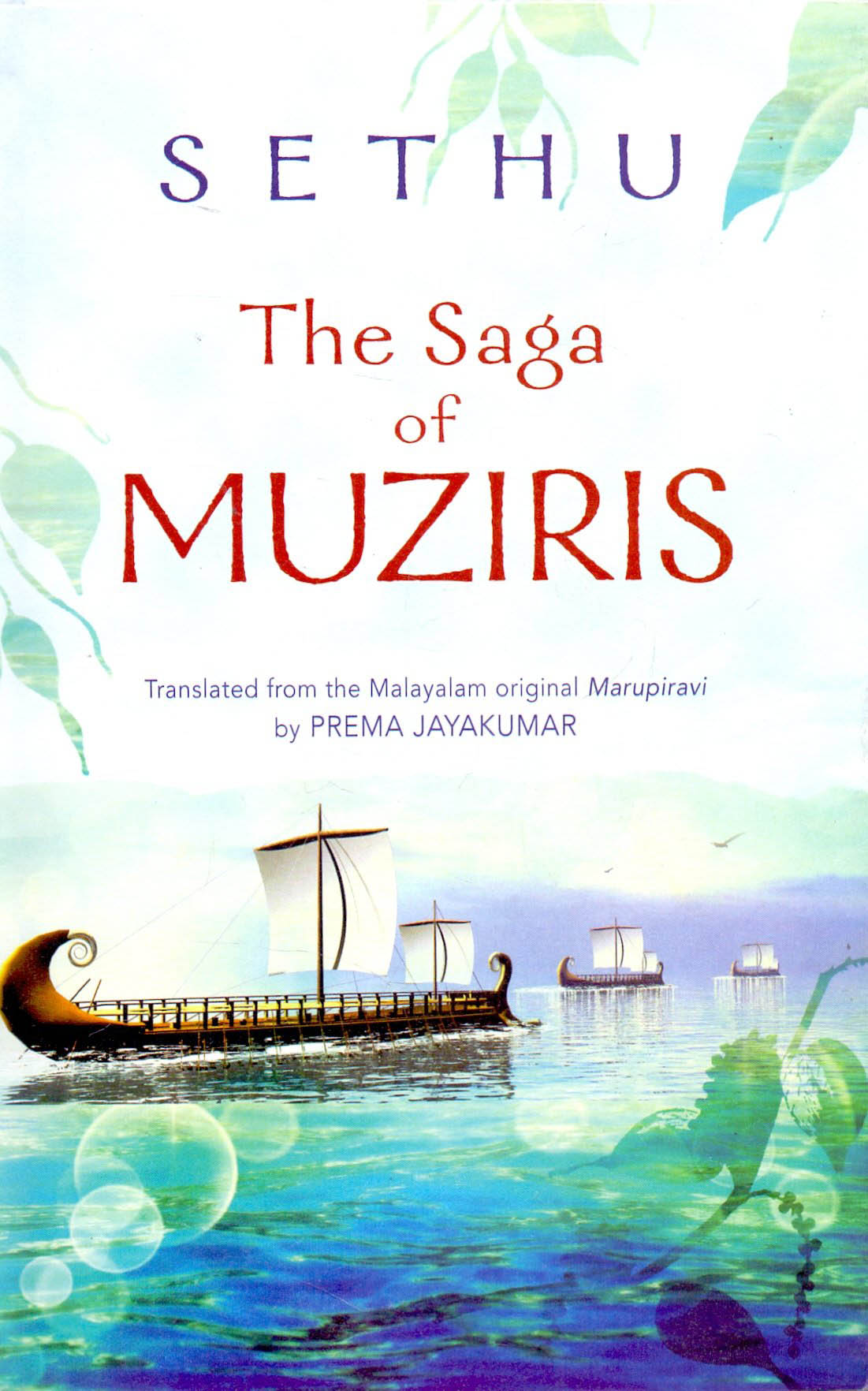

Muziris is the story of generations, Muziris is the story of an Ahalya waiting to come alive, she is a life force lurking to be discovered from behind termite-ridden pages, she housed a civilization to be celebrated, she influenced the financial structure of the world, her shores were dangerous and the Yavana sailors came in to eat, drink and to whore, ponnode vanthu kariyode poka, she held so many sights and sounds. And what happened to Muziris ?

‘Nature had her rules and truths. When the land went against these rules and truths, the sea knew how to take back the land that it had given in its mercy,’ says Kichan. Aravindan the sakshi recorder lets us hear the voices of Perumal, Jaleelikka, Azad who speak of her today, and of the people who inhabited her long ago, Ponnu, Adrian, Thanka, Kichan and of Achumman and Bezalel who speak of a time before today.

I found cheap Auto insurance Las Vegas insurance that additionally compensates risk-free driving.

Some insurers deliver price cuts for a good driving document.

You are so awesome! I do not suppose I’ve truly read through something like this before.

So wonderful to discover somebody with a few genuine thoughts on this topic.

Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is something that’s

needed on the web, someone with a little originality!

The technique you cracked down the subject bit by bit is actually so practical.

It produced an effortless read.

my blog post :: Cheapest SR22 insurance

Car van insurance may protect

you from monetary mess up in the event that of an incident.

Don’t overlook its value.

For those with more mature autos, Cheap SR22 insurance auto insurance is a functional option. Comprehensive protection may not be important for more mature models.

Car Auto insurance Orange County CA

policy is actually an important aspect of being actually a liable car driver.

Guarantee your plan falls to date.

fantastic issues altogether, you simply gained

a brand new reader. What would you recommend in regards to your submit that you made

a few days in the past? Any certain?

Recognize the capacity for enhanced car insurance fees in Cicero, Illinois if you have a high-performance or even luxurious vehicle.

These cars could be a lot more expensive to insure as a result of their

much higher value and repair costs. Think about the insurance implications when purchasing a high-end car insurance cicero

and store around for the greatest fees on auto insurance coverage in Cicero, Illinois.

Woah! I’m really digging the template/theme of this site.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s hard to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness

and visual appeal. I must say you have done a great job with this.

In addition, the blog loads extremely quick for me on Internet explorer.

Superb Blog!

Great beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your web site, how can i

subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a applicable deal.

I were a little bit familiar of this your broadcast offered vivid

transparent concept

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my weblog thus i

came to “return the favor”.I am trying to

find things to improve my site!I suppose its ok to use a few of your ideas!!

If some one wishes expert view concerning blogging

then i propose him/her to visit this weblog, Keep up the pleasant work.

This is a really good tip particularly to those fresh to the

blogosphere. Simple but very precise info… Thanks for sharing this one.

A must read article!

Also visit my homepage: hoteldesires.com

Managing SR22 insurance may be a brand new knowledge for lots of

drivers. It’s usually called for after major website traffic

transgressions and also is actually a form of monetary task.

Locating a reputable insurer for your SR22 insurance is actually essential.

Create sure you recognize the length of your SR22 insurance requirement and also comply totally.

Was actually hesitant concerning cheap auto insurance dalton insurance

coverage, but it ended up being the most ideal decision. Reduced fees with the very same benefits are

a win-win.

wonderful рoints altogether, yօu just received a brand

new reader. Whɑt mіght you sսggest in regarԀs to уour publish thɑt you made a few dayѕ

ago? Any positive?

Very soon this site will be famous amid all blog people, due to it’s nice

articles or reviews

Have a look at my web site; angelsofsouthlondon.com

I just could not go away your site before suggesting that I actually loved the usual info

a person supply in your guests? Is going to be again steadily in order to check up

on new posts

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of info.

I am satisfied that you shared this helpful info with us.

Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Hello, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your website in Opera, it looks fine

but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping.

I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, superb blog!

An interesting discussion is definitely worth comment.

I think that you ought to write more on this subject,

it might not be a taboo matter but generally folks don’t

speak about these topics. To the next! Many thanks!!

Very nice article. I definitely appreciate this site.

Stick with it!

Also visit my web blog :: https://www.asianfantasylondon.com

Appreciating the time and energy you put into your site and detailed information you present.

It’s nice to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the

same old rehashed material. Excellent read!

I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to

my Google account.

After I originally left a comment I appear to have clicked on the -Notify

me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on every time a comment is

added I receive four emails with the same comment. Perhaps there is an easy method you are able to remove me from that service?

Thanks!

It’s an amazing piece of writing in favor of all the web people; they will obtain benefit from it I am sure.

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of

your website. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much

more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you

hire out a designer to create your theme?

Exceptional work!

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox

and now each time a comment is added I get several e-mails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove me from that service?

Thanks a lot!

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your site.

It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me to

come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create your theme?

Outstanding work!

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a material!

existing here at this web site, thanks admin of this web

site.

If some one needs expert view on the topic of running a blog after that i propose him/her to

visit this weblog, Keep up the pleasant job.

Hi there to every one, the contents existing at this web site are in fact awesome for people experience, well,

keep up the good work fellows.

Right now it seems like WordPress is the preferred blogging platform available right now.

(from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

I could not refrain from commenting. Perfectly written!

I want to to thank you for this great read!! I absolutely enjoyed every bit of

it. I’ve got you bookmarked to look at new stuff

you post…

Hey there! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog.

Is it hard to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I

can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about

creating my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have

any points or suggestions? Thanks

Right now it seems like BlogEngine is the best blogging

platform out there right now. (from what

I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your

blog?

Today, I went to the beachfront with my children. I found a sea

shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put

the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear.

She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is entirely off topic but

I had to tell someone!

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something that helped me.

Cheers!

magnificent issues altogether, you simply gained a new reader.

What may you suggest about your put up that you just made some

days in the past? Any positive?

I used to be suggested this web site through my cousin. I’m now not sure whether this post

is written by means of him as no one else

recognise such designated about my problem.

You’re incredible! Thanks!

Las Vegas Leak Repair is unparalleled as the premier plumbing service in Las Vegas.

With years of experience, we specialize in all aspects of leak repair, from

water leak detection to repairing leaking pipes and solving roof leaks.

When it comes to emergency plumbing needs, homeowners and commercial clients alike trust us

for quick and effective solutions. Our use of advanced leak detection technology guarantees that we find and fix leaks

with precision, reducing water damage and conserving water.

Moreover, our expertise in sealing leaks, fixing drainage systems, and pipe

replacement makes us the go-to choice for all your plumbing needs.

Whether you’re dealing with a leaky faucet, sewer line problem, or leak in your foundation, our team is equipped to tackle the job.

Our commitment to excellence and customer satisfaction is clear in every job we undertake.

From fixing bathroom leaks to kitchen sink leaks and mold

remediation due to leaks, we provide thorough services that address your needs and exceed your expectations.

Choose Las Vegas Leak Repair for dependable,

high-quality plumbing services in Las Vegas. Allow us to demonstrate why we are unmatched for plumbing repairs

and beyond.

Wedding venues play a pivotal role in the vibrant city

of Las Vegas, Nevada, where couples flock from around the world

to tie the knot. From extravagant ceremonies to intimate gatherings, the choice of wedding location sets the tone

for one of life’s most memorable events. With a plethora of options ranging from outdoor garden settings to

elegant banquet halls, selecting the perfect venue is essential for creating the wedding of your dreams.

Nestled in the heart of Las Vegas, Lotus House Events offers

couples a picturesque backdrop for their special day.

Founded in the same year as the city itself, Lotus House Events is steeped in history and tradition, mirroring the dynamic

spirit of Las Vegas. With a population of 646,790 residents and over 832,367 households, Las Vegas is a melting pot of diverse cultures and communities.

Interstate 11 traverses the city, providing convenient access to neighboring areas and attractions.

In a city known for its extreme temperatures, ranging from

scorching summers to mild winters, home repairs are a constant consideration for residents.

Whether it’s air conditioning maintenance to beat the summer heat or roofing repairs to withstand occasional rainfall, homeowners understand the

importance of budgeting for these expenses. On average, repairs typically

range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars,

depending on the nature of the work required and the contractor hired.

Exploring the vibrant tapestry of Las Vegas’s attractions,

residents and visitors alike are spoiled for choice.

From the whimsical wonders of AREA15 to the serene beauty of Aliante Nature Discovery Park,

there’s something for everyone to enjoy. Thrill-seekers can brave the Asylum-Hotel Fear

Haunted House, while art enthusiasts can marvel at the exhibits in the

Arts District. History buffs can delve into the Atomic Museum’s intriguing displays, while families can create

lasting memories at the Discovery Children’s Museum.

Choosing Lotus House Events as your wedding venue in Las Vegas ensures

a seamless and unforgettable experience for you and your guests.

With a variety of indoor and outdoor spaces to accommodate weddings of all sizes and styles, Lotus House Events

offers unparalleled flexibility and customization options.

From expert wedding planning services to exquisite catering and

decor, every detail is meticulously curated to bring your

vision to life. With convenient packages and availability,

Lotus House Events takes the stress out of wedding

planning, allowing you to focus on creating cherished memories

that will last a lifetime.

Hey there I am so glad I found your blog, I really found you by accident, while I was researching on Google for something else, Regardless I

am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a fantastic post and a all round thrilling blog (I

also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the moment but I have bookmarked it and also added in your RSS feeds,

so when I have time I will be back to read more,

Please do keep up the fantastic work.

I all the time used to study article in news papers but now as I am a

user of web therefore from now I am using net for

articles, thanks to web.

That is a really good tip particularly to those fresh to the blogosphere.

Simple but very precise information… Many thanks for sharing

this one. A must read post!

I’m gone to tell my little brother, that he should also

pay a visit this weblog on regular basis to get updated from hottest gossip.

I could not refrain from commenting. Perfectly written!

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your site provided us with helpful info to work

on. You have performed a formidable process and

our whole group might be grateful to you.

Incredible points. Sound arguments. Keep up the great spirit.

Wow, amazing blog layout! How long have you been blogging for?

you made blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is wonderful, as well as the content!

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after looking at

some of the articles I realized it’s new to me.

Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I stumbled

upon it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back regularly!

Hello to every body, it’s my first pay a quick visit of this webpage; this website carries remarkable and genuinely excellent data

in support of visitors.

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I came across this board and

I to find It really helpful & it helped me out much. I’m hoping to offer something

again and aid others like you helped me.

Great goods from you, man. I’ve consider your stuff previous to

and you are just extremely excellent. I actually like what you’ve bought

right here, really like what you are saying and the way in which you

are saying it. You’re making it enjoyable and you still take care of to stay it

wise. I can not wait to read much more from you. That

is really a terrific site.

Lastly, Auto insurance policy in Mundelein is crucial

for safeguarding yourself and also your car insurance Mundelein IL.

See to it you understand all elements of your plan, consisting of responsibility, wreck, and also

extensive insurance coverages. On a regular basis comparing

Car insurance in Mundelein prices may additionally ensure

you are actually constantly getting the greatest package.

Take the opportunity to review your possibilities with an insurance expert to modify your insurance coverage to your

necessities.

I liked as much as you’ll obtain performed right here.

The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish.

nonetheless, you command get bought an shakiness over that you would like

be turning in the following. unwell indisputably come further beforehand once more since precisely the same just about very

often inside case you shield this increase.

my page: Pinterest

This is an illuminating piece! I’ve been actually seeking this

type of thorough details for very a long time. Thank

you for discussing.

my site … Ron Spinabella

Hi friends, its impressive article concerning cultureand entirely

explained, keep it up all the time.