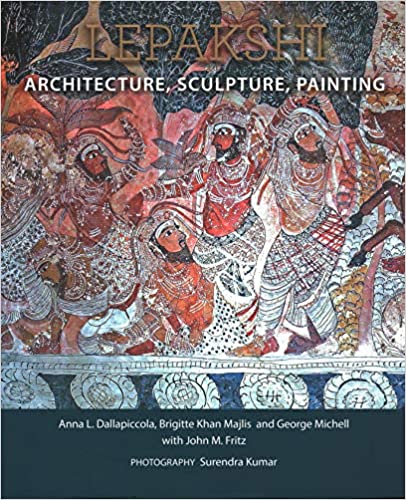

This book presents a fairly comprehensive primary coverage of the heart of the Lepakshi temple town where lay its religious and trade basis. Its richly painted ceilings take us beyond an identification of religious iconography to tell us about the shifts in the perceptions of myths and enliven the history of textiles and trade. Rather tantalizingly, the gameboards carved into its floors invite us to look up how they worked, and ponder further on what rhythms made Vijayanagara society tick. The depth and richness of Vijayanagara art and architecture have radically altered our perception of what constituted the public, which myths were important, how social change was accompanied by a change in myths and legends, and how cleverly the past was altered and reinvented to fit the requirements of its age. George Michell, John Fritz and Anna Dallapiccola have presented one compelling study of this period after another over the past thirty years or more, involving a network of other scholars—this time, with textile historian, Brigitte Khan Majlis; and with the photographic documentation by Surendra Kumar.

The monument needs to be recognized as an outstanding example of the Vijayanagara period architecture and art. The temple at Lepakshi is dedicated to Virabhadra, and was sponsored by Virapanna, the governor or representative of the province of Penukonda (Rayalseema) under the Vijayanagara King Achyutaraya who reigned from 1520 to 1542 (that is about the time when Humayun and Sher Shah Suri were in Delhi), and a portrait that still survives at Lepakshi is said to be of Virapanna, the temple’s patron. Virabhadra, the principal deity of the Virashaivas, was adopted by the merchant communities (Balija, Shetty, Chetti) at Lepakshi. The Virashaiva community rose to prominence in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries as a powerful alternative to a divisive casteist Brahmanical social structure and, merchants apart, drew its largest subscription amongst Gavli, Golla, Kuruba and Dhangar pastoralists across the Deccan. Just as this temple celebrates and integrates the localized traditions via Virashaiva stories into a more mainstream Puranic apparatus, elsewhere in Vijayanagara domains we have seen temples that integrate stories of foreign merchants, forest-dwellers, warrior castes and so on.